WHERE IS THE STARTING POINT OF CUBAN ART?

– By Virginia Alberdi Benítez –

The strength of the images of the Cuban contemporary artists and the interest they awaken among collectors, critics and European viewers, as evidenced by the experience of the Artemorfosis Gallery, in Zurich, have a backup history that dates back to the beginnings of the establishment of the nation in the Antillean island, when Cuba was a territory belonging to the Spanish colonial empire.

Cuba is called the key for the New World, because of its strategic position at the entrance of the Gulf of Mexico, and it is difficult to define a starting point to determine the emergence of artistic expressions with their own identity. During the sixteenth century and a good part of the XVII century, Cuba was a station in the passage of trade between America and Spain and only the establishment of religious institutions and the need of decorating mansions inhabited by the colonial authorities justified the presence of works of art, many of them of religious content, brought from Europe.

This does not mean that the image of Cuba, of its first urban sites and its landscapes, would not seduce the interest of foreigners, especially after the XVIII Century. A Frenchman, Dominique Serres, gave a graphic testimony in 1762 of the taking of Havana by the English soldiers. An artist who was born in the thirteen British colonies in North America, Elias Durnford, represented in lithographs his view of Havana and its surrounding area between 1784 and 1765.

In subsequent decades and until the late nineteenth century, several traveler artists showed the views of cities and customs in lithographs that are very appreciated at the present time. Such are the cases of Eduardo Laplante and Federico Mialhe. Also the Spanish artist, Vincent Patrick Landaluze, dedicated his work to represent vernacular scenes.

But, for a true Cuban, the credit belongs to José Nicolás de la Escalera (1734-1803), who was born in Havana from a Spanish father and a third-generation Cuban mother. Although his painting is framed in religions subjects and portraits of authorities and personalities of the colonial society, and generally follows the figurative patterns of the European art of the XVIII Century, it is possible to notice to observe in his paintings an accumulation of elements responding to a style that was starting to grow in other colonial territories of the time, subsequently called “American baroque”.

José Nicolás de Escalera y Domínguez: Santa Bárbara (ref: dev.ecured.cu)

Escalera’s influence is present in the church of Santa Maria del Rosario, a small town in the outskirts of Havana, and in the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, which exhibits his Holy Trinity, and the portraits of Don Luis de las Casas, one of the most enlightened rulers of the island, and Luis Peñalver, bishop of the Louisiana and Florida, Spanish territories by that time.

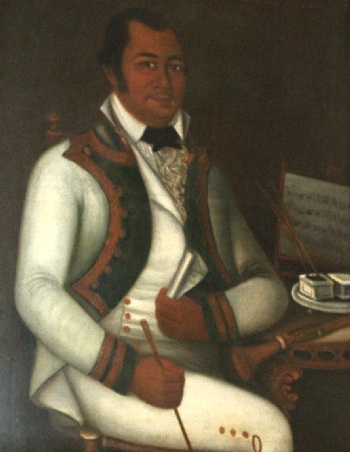

Even more a Cuban, due to his lineage, Vicente Escobar (1757-1834) was the first man of mixed-race in achieving a certain reputation among the wealthy classes by his painting talent. Those people, for once at least, turned their eyes toward a black musician friend of Escobar, who lived in the city of Cardenas, because of what is possibly the first academic portrait of an Afro-Cuban descendant in the Cuban culture. In the times of Escobar, other mixed-race individuals dedicated to painting. They had no training and served the interests of the official authorities, the clergy and the merchants who began to profit from the slave and the export of sugar.

Vicente Escobar: Jacke Quiroga (ref: galeriacubarte.cult.cu)

But at the dawn of the nineteenth century, when the plantation economy and the sugar industry were consolidated, and the Spanish colonial empire was defeated in many countries of the Spanish America, the social structure of the island was drifting toward a reproduction of the cultural and educational practices of the metropolis in which it was possible to observe, however, the birth of a creole identity.

Among the institutions which have emerged at that time was the Academy of San Alejandro, founded in Havana in 1818. There are historians who have speculated that the Academy was created to take the black and mulattoes individuals out of the hierarchy reached in the market of the artistic orders.

The first director of the Academy was a Frenchman, Jean Baptiste Vermay (1786-1833), disciple of the famous Jacques Louis David. The pedagogic plan was based on the romantic Aesthetics, evident in the landscape painting, and that was promoted as the invariant ideal of hedonism and the distancing of everything that could involve a social questioning. The right thing was to imitate the French schools of Barbizon and Fontainebleau and maybe to approach the Hudson River American School. River. As remarking painters throughout the nineteenth century we can mention Esteban Chartrand, Valentin Sanz, and later, Juan Jorge Peoli, José Arburu y Morell, Miguel Angel Melero and Guillermo Collazo.

Esteban Chartrand y Dubois: Paisaje (ref: dev.cured.cu)

Being a Cuban was not yet to express the Cuban features in its full intensity and originality. But, at least, there was a progressive approach to what would become the National identity, a process we must consider as a starting point to understand the backgrounds of the contemporary Cuban visualization.

Havana, Summer 2015